Visit our sponsor and earn money in your PayPal wallet

Shoppers are adding to cart for the holidays

Over the next year, Roku predicts that 100% of the streaming audience will see ads. For growth marketers in 2026, CTV will remain an important “safe space” as AI creates widespread disruption in the search and social channels. Plus, easier access to self-serve CTV ad buying tools and targeting options will lead to a surge in locally-targeted streaming campaigns.

Read our guide to find out why growth marketers should make sure CTV is part of their 2026 media mix.

THE BIG PICTURE

For the first time in recorded history, not a single major city on Earth is considered affordable anymore. According to Chapman University's Demografía International Housing Affordability Report, which tracks 95 major cities globally, every market has crossed the threshold into unaffordable territory. This isn't just a housing story—it's a fundamental reshaping of the global economy and middle-class prosperity.

The numbers tell a stark tale: homes that once cost 3 times the typical household income now average 5 times or more. In cities like Hong Kong, Sydney, and Vancouver, that ratio has exploded to 14, 13.8, and over 9 times respectively. In Beijing and Shanghai, ratios routinely exceed 20-30 times median income.

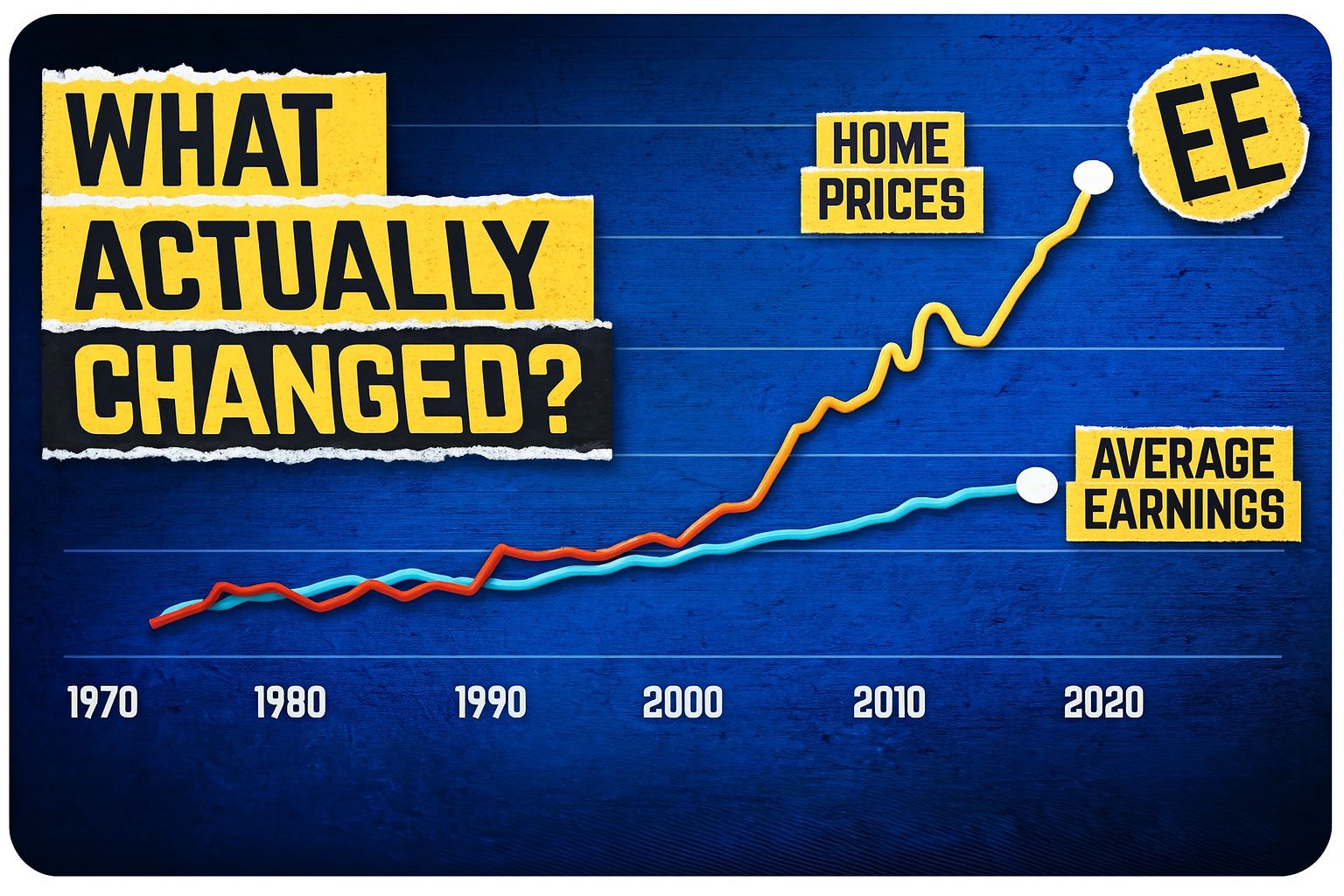

What changed? Three decades ago, nearly all these cities were affordable. Today, owning a home has shifted from a middle-class milestone to an impossibly distant dream for millions.

THE METRICS THAT MATTER

The Median Multiple: This critical ratio divides median home prices by median household income. A healthy market sits around 3.0. Here's where major markets stand today:

Hong Kong: 14.4x (Impossibly Unaffordable)

Sydney: 13.8x (Impossibly Unaffordable)

Vancouver: 9+ times (ranked 4th least affordable for 18 straight years)

Greater London: 9.0x

Los Angeles & San Jose: Impossibly Unaffordable category

Australia average: Near 10x median income

UK average: 5.6x (double the 1990s level)

United States average: 4.8x (up from 3.9 pre-pandemic)

Pittsburgh (most affordable US city): 3.2x—once normal, now a miracle

The report introduced a new category this year: "Impossibly Unaffordable" for cities where homes cost more than 9 times median income. Twelve cities now fall into this category.

THE CHAIN REACTION: HOW WE GOT HERE

1. From Shelter to Asset Class

Thirty years ago, a house was shelter. Today, it's a global investment vehicle. As wealth concentrated at the top, the wealthy didn't buy more groceries—they bought assets. Housing became the perfect target: essential, easy to own, rent out, or borrow against.

2. Policy-Made Scarcity

Well-intentioned regulations—protecting green space, controlling sprawl, preserving neighborhood character—morphed into zoning limits, height caps, parking minimums, and endless approvals. These restrictions created artificial scarcity. Prices stopped reflecting construction costs and started reflecting policy-made limitations on supply.

3. The Money Flood

As interest rates fell and global cash supplies surged, capital chased the same limited housing stock. When investors could borrow at 3% and watch properties appreciate 7% annually, they didn't need to live in them—just own them. Institutional buyers purchased single-family homes in bulk. Foreign investors used property as wealth storage. A feedback loop formed: scarcity drove prices up, which attracted more capital, which drove prices higher.

4. The Wage Stagnation

While asset prices soared, wages flatlined. US median real wages have risen only 10% over 20 years, while home prices doubled, tripled, or quadrupled. In the 1990s, a single income could buy a family home. When dual incomes became standard, sellers adjusted—prices simply doubled to match. Dual incomes didn't make homes more affordable; they made the same homes cost twice as much.

5. The Debt Spiral

As the gap widened, buyers stretched into larger mortgages. Banks kept lending because rising prices made markets look safe. But every bigger loan approval meant buyers could bid higher, pushing prices up further—another self-reinforcing cycle.

6. The Pandemic Acceleration

Remote work scattered demand but didn't fix the core problem. Construction costs exploded, supply chains broke, inflation hit materials, and labor shortages slowed projects. When interest rates rose, borrowing got expensive—but prices didn't crash. Millions locked into ultra-low-rate mortgages refused to move, freezing supply. Government subsidies for first-time buyers only made people fight harder over the same limited homes.

THE REAL-WORLD IMPACT

On Households: Renters in major cities now spend 30-35% of income on housing—above the affordability threshold. The average first-time buyer is now in their late 30s or early 40s, a full decade older than their parents' generation.

On Labor Markets: When people can't afford to live where jobs are, they stop moving for opportunity. The US and Canada are experiencing "counter-urbanization"—people leaving productive cities for small towns. Cities lose teachers, nurses, tradespeople, and service workers. Housing lock becomes labor lock.

On Inequality: Existing homeowners accumulate wealth through scarcity, not labor. Global real estate value now sits at 3.5 times world GDP. Those who bought in face high debt, high risk, and constant economic anxiety. Those locked out face permanent renter status.

On Demographics: Families delay having children due to space constraints. Workers turn down better jobs because relocation costs are prohibitive. Younger generations stop saving—if ownership is impossible, why bother?

WHAT'S BEING DONE

Some countries are experimenting with solutions:

Supply-Side Reforms:

New Zealand: "Going for Housing Growth" forces councils to zone land for 30 years of demand

US: Minneapolis and California loosening single-family zoning to allow duplexes and small apartments

Singapore: Treats housing as infrastructure—90% homeownership through massive public housing program

Demand-Side Interventions:

Hong Kong & Wales: Heavy taxes on second homes (Wales up to 300% council tax premium)

Taiwan: Up to 45% tax on property sold within two years

Netherlands: Some municipalities ban investor purchases in certain neighborhoods

US: Proposed "End Hedge Fund Control of American Homes Act" would stop institutional ownership of single-family homes

THE BOTTOM LINE

This crisis isn't about one policy failure—it's a chain reaction of restricted land, cheap money, wage stagnation, and short-term fixes that made problems worse. The report's authors call it "an existential threat to middle-income households."

More construction alone won't solve this. We need to rethink who's buying homes, where they're built, and what kind of economy they're fueling. At its core, this is a story of massive capital flows drowning middle and low-income classes in a handful of asset markets.

Until that balance changes, the dream of homeownership will continue slipping away—not in one country, but across the developed world.

TRADE INSIGHT: Real estate now functions more like gold or treasury bonds than shelter—a store of value in an era of currency uncertainty. For traders and investors, this creates opportunities in REITs, construction materials, and alternative housing solutions. But for society, it represents a fundamental breaking of the post-war social contract.

The question isn't whether this is sustainable. It clearly isn't. The question is what breaks first—and what comes after.